by Maurizio Bernardelli Curuz

An elite overwhelmed by the great beauty of the Italian culture of the past, unable to react and be productive, as there is nothing of beauty left to produce. The only road open is the fatuity – sometimes intellectually profound and performed with Machiavellian perfection – of a dance of homage to the relics of the ancestors, who kill the soul by means of a melodramatically sublime disease. With a film which, in some points, achieves the highest levels of a formal elegance and Mannerism typical of the culture of Decadence, Paolo Sorrentino has produced a work of immense poetical, cultural and political value. The central theme is the sterility and castration produced by the Super Ego of a country frozen by the fear of failure and the satiation induced by the engulfing messages coming from the past. The film’s protagonist, like the artist in Moravia’s “Boredom”, suffers from creative sterility. Forty years before the events covered by the film (recounted more through allusion than actual narration), he had written a successful novel, and has since then become an interviewer – in other words, he has become a listener of those who create discourse – living only by night, progressing from party to party with other intellectuals who have failed on the human level, men of the cloth, foolish women on the make and promiscuous virgins.

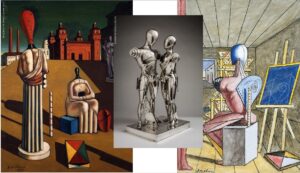

Physical sterility is portrayed in the husband of Elisa, the woman the protagonist loved in his youth without managing to hold onto the happiness he enjoyed with her, represented by fleeting flashbacks bathed in the light of a blue sea that open out before the writer’s eyes like painted ceilings. Intellectual sterility appears in the person of the left-wing feminist who churns out banal books, while spiritual sterility is represented by the figures of the churchmen, one of whom is only capable of illustrating cookbook recipes, a task to which he brings liturgical precision. From the semantic point of view, the film’s key image is provided by the sequence showing the performance of a young female artist. Before the usual milieu of guests, in the Roman countryside she dashes naked towards an ancient Roman aqueduct and strikes her body hard against its base. The Roman aqueduct symbolises the barrier preventing any attempt at modern creativity. The ghosts that prevent Italy from achieving are models that demand incredibly high standards, inducing impotence – remember Brancati’s Antonio and his father’s expectations? – and the inability to generate offspring. It should be no surprise that during a nocturnal visit to a palazzo by the protagonist and a stripper, vainly expected to provide a life-giving injection of proletarian carnality, Sorrentino presents us with Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Woman, which appears as a ghostly image. Raphael’s significance is that of the painter who attained an unrivalled level of perfection. And who thus provokes a new form of sterility or, rather, the mindless production of stylistic clones of beauty. Sorrentino immerses the spectator in an exquisite flow of atmospheres with echoes of Luchino Visconti – in the gloomy poetry of suffocating interiors – who in turn leads back to the D’Annunzio of the Child of Pleasure; he combines Andrea Sperelli with Visconti, an attenuated Felliniesque expressionism and surprise plot twists à la Almodovar. And last but not least, in the dramatic image of the saint in the finale, he gives us the lights and faces of Caravaggio, the only way towards the violence that is the foundation of truth, so similar to the Baroque certainty of death.

“Clic” i like Stile arte

“The Great Beauty”- What is the meaning of Paolo Sorrentino’s “The Great Beauty”?

More from NewsMore posts in News »